Atomic Theory: What are Atoms?

Written By: Arman Momeni

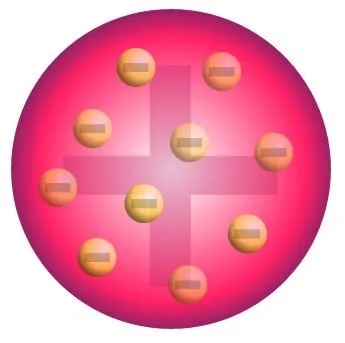

Atomic theory started with Dalton. His main revolutionary point was that matter is composed of tiny indivisible particles called atoms; however, Dalton only touched the surface. He failed to dive further and explore what resides inside of the atom. Later on, J. J. Thomson, another brilliant mind, proposed that mass and charge were distributed evenly throughout an atom, and he proposed the plum pudding model, founding the electron. In his model, the electrons were the plums, and the pudding was positively charged. The electron was the first sub-atomic (smaller than atom) particle to be discovered. At the time of its discovery, the only information about it was that it held a negative charge, which canceled out the positive charge that comprised the rest of the atom.

J. J. Thomson’s plum pudding model of the atom

The next great discovery was made by Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford set out to prove Thomson’s model, but instead he falsified it through his gold foil experiment. The gold foil experiment consisted of a gold foil, and alpha particles, which were a type of radioactive particle with four times the mass of a hydrogen atom. If Thomson’s model held true, and atoms held a uniform charge, then scientists expected that all of the alpha particles would pass right through the gold foil. To their surprise, a small number of the alpha particles bounced off the foil with heavy obtuse angles. In order to explain his results, Rutherford developed a new model of the atom. Rutherford concluded that atoms were mostly empty space, but they all had a very concentrated small interior, which he called the nucleus. The nucleus, in Rutherford’s theory, is a tiny, dense, and central core of the atom that is composed of protons (positive charge) and neutrons (neutral charge). This model was called the nuclear model.

Rutherford’s Gold Foil Experiment

While Rutherford’s theory mostly held true, there were a couple of flaws. If the protons are all positively charged (and like charges repel each other), why didn’t the nucleus tear apart? Or, if opposite charges attract, why didn’t the negatively charged electrons collapse into the positively charged nucleus?

Niels Bohr provided the answer to the second question, stating that electrons have a fixed energy and orbit around the nucleus. While Bohr’s model explained a lot at the time, we know that his model was not entirely correct.

The Bohr model of the atom

Later on, in 1926 Erwin Schrodinger, an Austrian physicist, took the Bohr model, and advanced it even further. Schrodinger used mathematics to express the probability of finding an electron in a certain position. This model was called the quantum mechanical model of the atom.

Now if you are confused by atomic theory, don’t fret. The basics that you need to know is that all matter, as stated above, is composed of atoms. While incomprehensibly small, atoms are not the smallest components of matter. Our current understanding states that atoms are made of protons (positively charged particles), neutrons (no charge), and electrons (negatively charged particles); these are all sub-atomic particles. While neutrons and protons are the same mass, the electron is far smaller. The electron’s mass is so small that it is denoted as negligible (essentially 0). Past the proton, neutron, and electron, are quarks. Quarks are elementary particles that combine to form composite particles called hadrons; protons and neutrons are the most stable type of hadrons. The electron, however, is only composed of a single quark. As of now, quarks are the smallest proven particles, however scientists have been working on breaking down the atom even further through string theory.

All of the currently known elementary particles. There are 6 types of quarks!