Veggiecine: A Novel Approach to Suturing

Written By Kaushik Valiveti

One of our biggest missions at Science Rewired is to stress to you all that science is a living, breathing entity, always evolving and never, not even for one day, remaining stagnant. It’s a relentless journey, where each discovery provides a stepping stone to understanding more about the confusing world we live in. And fortunately, there’s one thing that seems to be powering it the most in this day and age: the indomitable curiosity of young scientists all over the world with new visions. As appreciation for all the truly admirable things young people are accomplishing, I wanted to highlight an instance of true entrepreneurship and critical thinking in the realm of science: beet sutures by 17-year-old Dasia Taylor.

Let’s do a quick introduction.

Standard dermatological suture placed on patient. Picture shows one week of recovery post-op.

Sutures are threads used in surgery to close incisions. Their main functions are to promote wound healing, prevent infection, and minimize scarring. Right now, sutures are made of synthetic and metallic materials, including polyglolic acid, polyglactin 910, and titanium. Though they are usable, many sutures cause uneasiness for the patient post-operation. One of the biggest examples of this is tissue reactivity. When foreign materials are implanted in surgery, our body's immune system and localized tissues may react in various ways, ranging from inflammation ( Cells of the immune system, such as macrophages, are sometimes recruited to the site of the suture to remove the foreign material. This can lead to unpredictable consequences, like swelling or redness, at the site of contact) to granuloma formation (the body may additionally form small patches of inflamed tissue called granulomas around the suture material.)

But perhaps one of the most dangerous consequences of using synthetic sutures is the risk of bacterial infections developing. Surgical site infections, a common subgroup of hospital infections, are highly likely to form because of incorrect suturing procedures. Oftentimes, it’s too late to identify if a bacterial infection has spread because of misplaced sutures or lack of sterilization when implementing them.

So what did Dasia Taylor’s beet sutures do about this?

Dasia was well aware of this insurmountable problem in the medical community and decided it was time for change. According to a recent interview with her, “Human skin is naturally acidic, but infected wounds have a higher, basic pH level. I found that a natural indicator like beet juice—applied to the surgical suture—would change color based on a patient’s skin pH level, revealing infection. I found a list of vegetables and their corresponding pH levels and beets were the first one that I found that I thought might work.”

Beet juice, because of its high anthocyanin levels, can change color in response to the environmental pH, making it an excellent indicator. This specifically occurs because the beetroot juice’s conjugate acid has a high threshold of absorption spectra, allowing humans to see changes in color so that they could identify promptly when the bacterial infection manifested and take preventative measures.

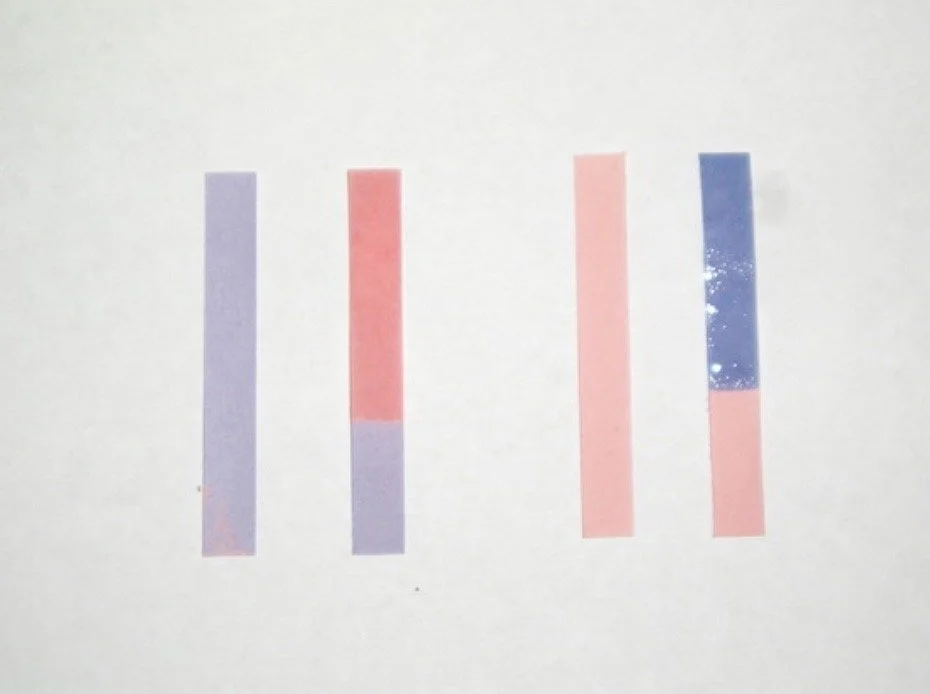

Red litmus paper turning blue in basic conditions and blue litmus paper turning red in acidic conditions.

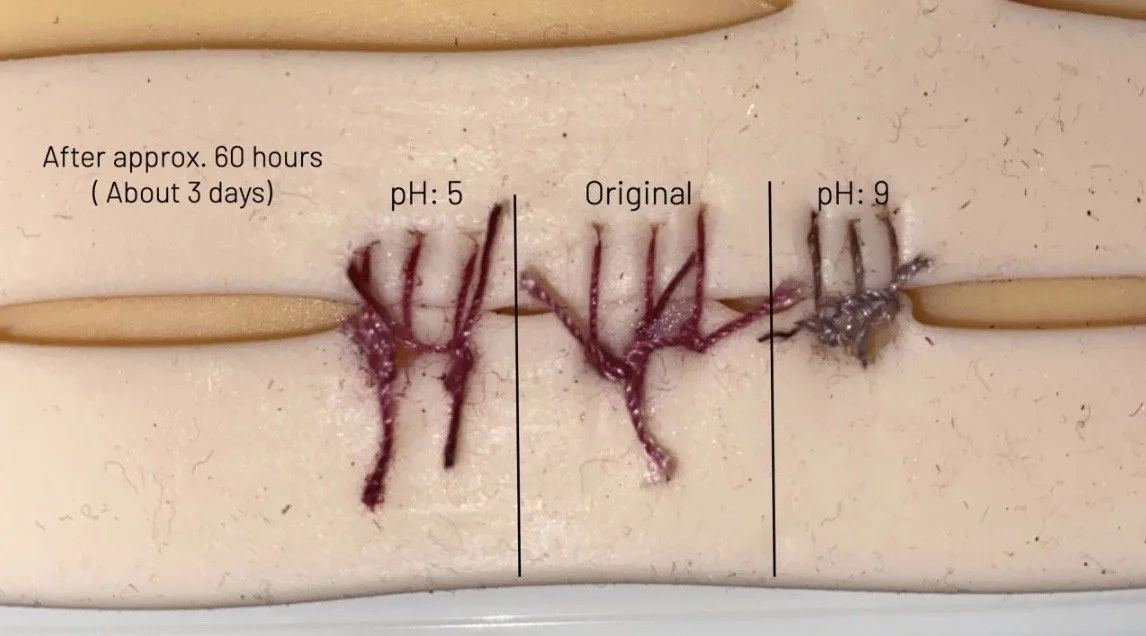

Beet sutures turning more blue because of increased alkaline environment.

By creating a test that could readily detect dermatological pH changes in the body while also being non-invasive, Taylor contributed extensively to the fields of chemistry and natural science. She serves as a beacon of inspiration for young scientists around the world. Taylor now attends Iowa University, educating students about health disparities and one day hopes to bring her patented sutures to medically deprived countries. By channeling as much passion and knowledge into your field as she did in hers, you too can make something revolutionary—even if it’s as crazy as vegetable stitches!

Works Cited:

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, April 6). chemical indicator. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/chemical-indicator

Dasia Taylor uses beets to improve post-surgical care. University of Iowa. (n.d.). https://magazine.foriowa.org/story.php?ed=true&storyid=2172#:~:text=University%20of%20%20Iowa%20student%20Dasia%20Taylor%20discovered%20a%20new%20use,a%20patient's%%2020skin%20is%20infected.

Huynh, A., & Krupa, M. (2021, April 17). A student harnessed the power of beets to make healing from surgery safer -- and more equitable. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/17/us/student-beets-color-changing-sutures-wellness-trnd/index.html

Magazine, S. (2021, March 25). This high schooler invented color-changing sutures to detect infection. Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/high-schooler-invented-color-changing-sutures-detect-infection-180977345/